Israeli settlements are illegally dumping wastewater onto Palestinian villages, farmlands and agricultural lands. This practice has devastating effects on the Palestinian lands, both reducing and preventing any agricultural production, livestock farming and infecting previously safe drinking water. The accumulative effect of these issues has resulted in an economic downturn, increases in disease and health problems, an increase in poverty and often the slow migration of Palestinians to other areas where they have more potential for earning and farming which only further compounds the issue of internal displacement. The following case study analyses the effects of this practice on two Bethlehem Governate areas, Wadi Foukin and Nahaleen.

|

|

Figure 1: An olive that has been attacked by the harmful insects that live in the contaminated water sources.

|

Settlements in the West Bank:

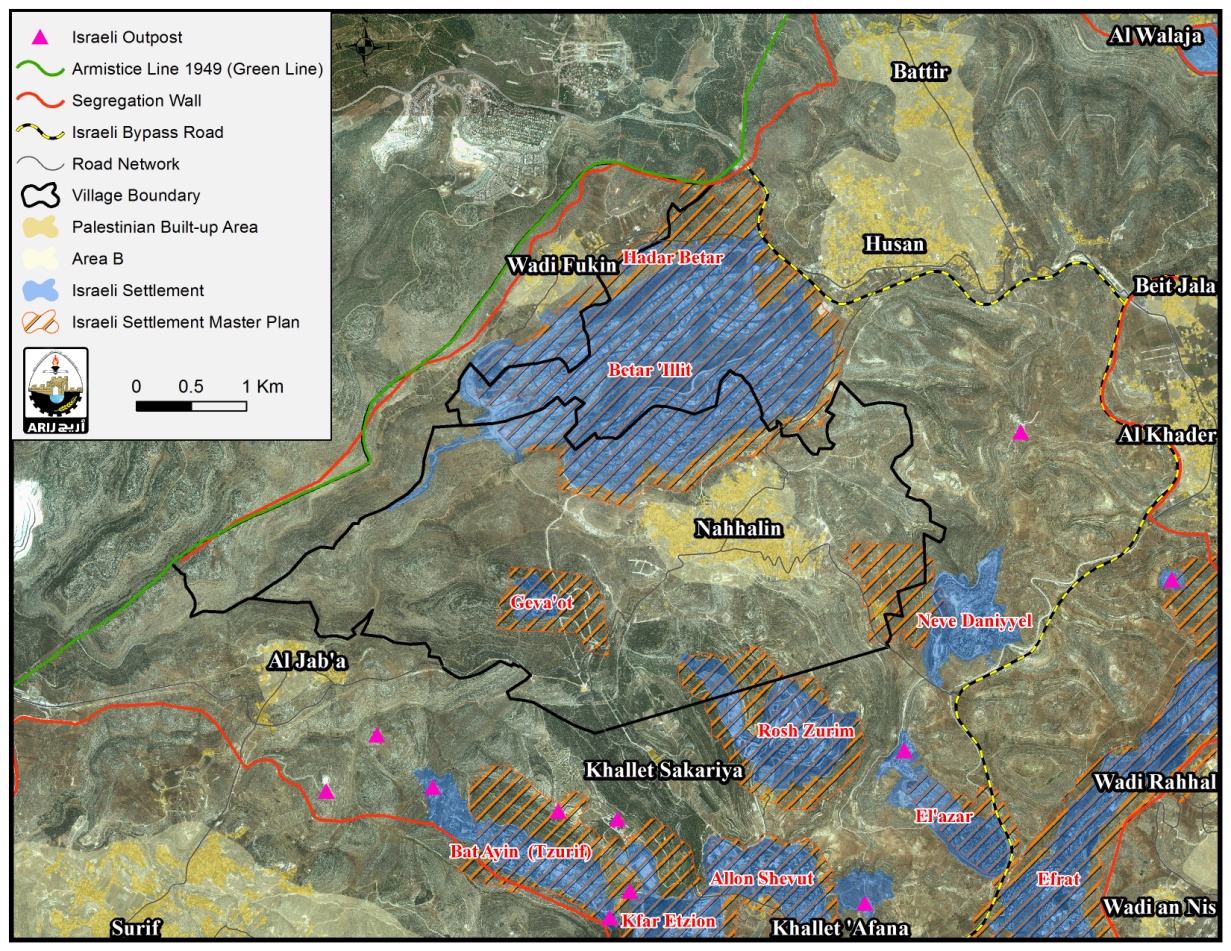

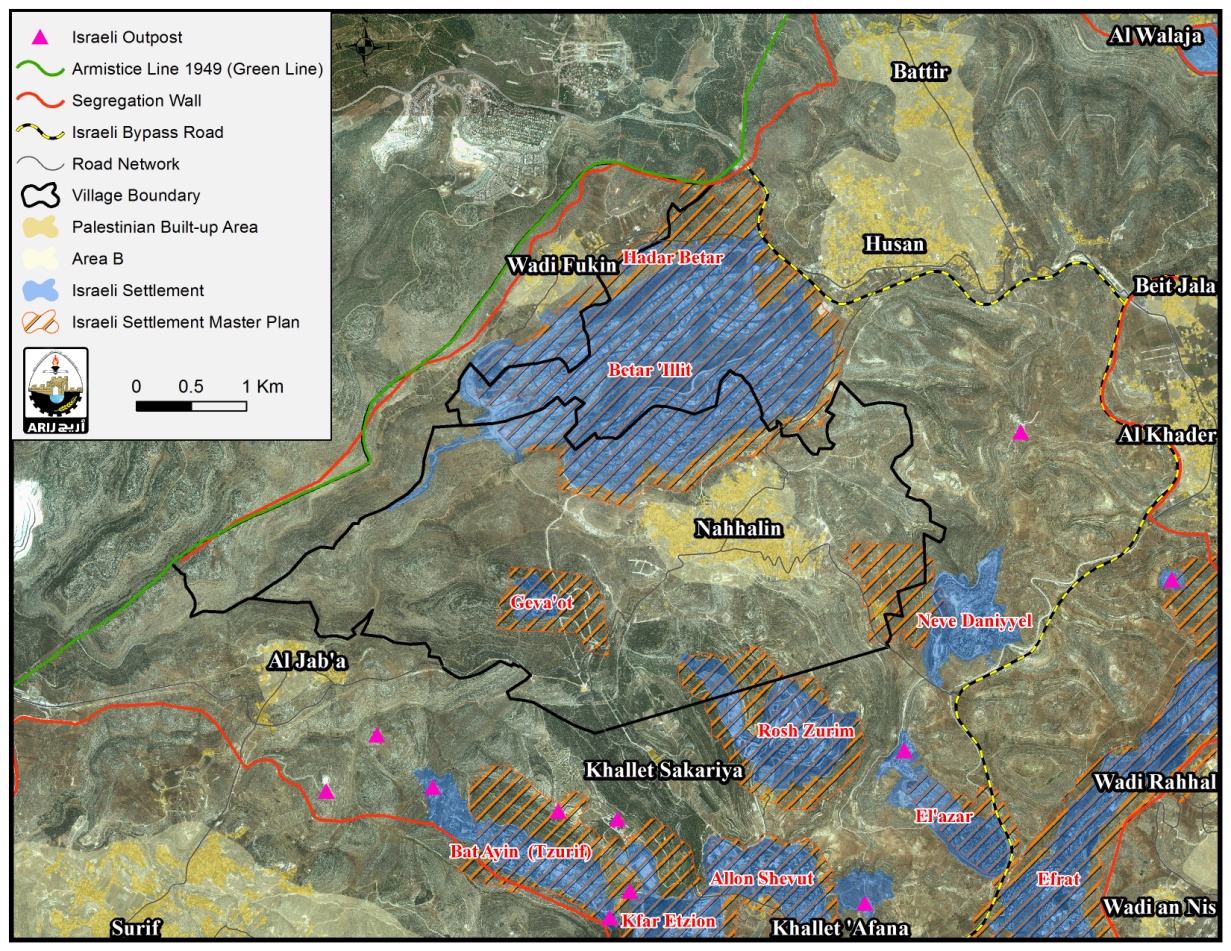

The existence, expansion and further building of settlements in the West Bank have long been recognized as illegal under international law. There are now 23 illegal settlements located in the Bethlehem Governate, with a population range of less than 100 to nearly 40,000. Each settlement appropriates land and resources from the Palestinians, often taking prime agricultural land or forested areas on which to build. The settlement Betar Illit is the biggest settlement in the governate; it had a population of 39,736 recorded in 2011 and was built in 1985 (Peace Now, 2001). The settlement is religion based and towards the end of 2012 a further 398 units of housing were authorized for development within the settlement, further extending boundaries. Eventually, Israel plans for this settlement to be absorbed into the wider area of Jerusalem, as demonstrated by the position and planned construction of the segregation wall. The segregation wall will eventually encompass the settlement areas under the pretence of security enclosing 10 settlements in the Bethlehem Governate and 5 Palestinian villages; Al Jab’a, Wadi Foukin, Nahaleen, Husan and Battir. The placement and final plan for the segregation wall is that this whole area will be self contained and separated from the West Bank, Israel’s defence remains that such measures are needed in an area that has a high concentration of settlers. However, the eventual construction will sever all ties of the villages with the main town of Bethlehem, preventing villages from accessing the services that Bethlehem provide and which they are unlikely to access from Israel service providers. The wall will also cut them off from receiving initiatives and projects such as wastewater treatment plants which can help in water scarce areas. A further problem is that the settlements also don’t have wastewater treatment plants and instead dump their wastewater onto the Palestinian villages, two that suffer the most are two that border with Betar Illit settlement, Nahhalin village and Wadi Foukin village.

|

|

Figure 2: Location map of Wadi Foukin, Nahaleen and Betar Illit

|

The issue with wastewater:

All inhabited areas produce wastewater; it is simply the water that is used in personal living, industrial processes, agriculture and sewage. The water itself can include a variety of substances which make the water unsafe for reuse such as; detergents, bleach products, soaps, industrial liquids including garage liquids, sewage and pesticides. Untreated wastewater is one of the biggest pollutants in the West Bank, contaminating streams, springs and other water sources. Not only do these products make the water undrinkable, it also damages the soil quality and damages crops and any young plants that it touches. This in turn can decrease the amount of agriculture that Nahhalin and Wadi Foukin are able to produce. Betar Illit has been dumping huge quantities of waste water on both villages. An estimated 80% of all water used results in waste water. If we assume an average of 300 litres used per person per day by Betar Illit, a low estimation compared to the 400+ litres that some settlements use, then 240 litres of it will become wastewater. For the whole settlement population this would create an estimated 9,536.64 litres of wastewater per day from Betar Illit being discharged onto Palestinian lands and villages. The affect is a lower the amount of produce and agricultural output that each area can have, thus lowering the economy and affecting things like unemployment rates, poverty and opportunity.

Village profiles:

Wadi Foukin and Nahaleen are both Palestinian villages located to the South West of the Bethlehem Governate. The area separating the 2 villages is the Israeli settlement Betar Illit. The population of each town is 1,200 and 6,827 respectively (PCBS, 2009). The Betar Illit settlement currently expands across 4699.8 dunums with 771.0 dunums of agricultural land; however the master plan for the settlement is expected to reach 5847.2 dunums (ARIJ GIS, 2013). The land on which Betar Illit sits is Palestinian land belonging to both the villages in question and local farmers, prior to the development of the settlement the land was used for agriculture. Both villages are surrounded and affected by the segregation wall. Their locality is within an area in which several settlements have been constructed and so citing security as a reason, Israel has begun plans for constructing the wall around the area forming an enclosure. Such extreme measures will greatly affect both villages effectively cutting them off from the rest of the Bethlehem Governate and preventing them easy access to the services available to them in Bethlehem such as health services and education. Eventually both villages will be included in Israel’s further extension of East Jerusalem placing them firmly within Israeli boundaries.

Wadi Foukin:

The village of Wadi Foukin is surrounded on 3 sides by illegal settlement Betar Illit. 9% (362.0 dunums) of its lands have been appropriated by the settlement and a further percentage by the building of the separation wall, which for 4.6km runs along Wadi Foukin land separating the village from a proportion of agricultural land. 92.7% of the land in which Wadi Foukin sits has been classed as Area C, limiting the extent to which Palestinians are able to develop the land and develop their infrastructure. According to the master plans for the settlement, further settlement expansion will expand the settlement boundaries from 4699.8 dunums to 5847.2 dunums (ARIJ GIS, 2013). This will take an extra 2% of the village’s lands in Wadi Foukin alone, equating to 458.9 dunums. Wadi Foukin’s agricultural sector equates to 60% of the villages economic activity. However with the reduction of land available for cultivation which currently stands at only 1023.5 dunums, agriculture will be greatly reduced leading to higher unemployment rates. 40% of the agriculture workers are already unemployed and 65.2% of the village overall is not economically active from the ages of 10 years and up (ARIJ, 2010). It is also expected that as the settlements continue to expand the development of Israeli only roads connecting settlements to one another will further take land from the Palestinians. The illegal dumping of Betar Illit’s wastewater on this village’s lands is having much the same effect as that of the land grabbing.

|

|

Figure 3: The wastewater pipe leading onto Wadi Foukin’s lands complete with sewage remains.

|

Wadi Foukin has one pipe which expels wastewater directly onto Palestinian hills from the Betar Illit settlement and an underground water well that is used for collecting wastewater but which periodically floods due to the quantity of wastewater being discharged into it. The majority of the waste that is released is sewage waste, as can be seen in the photo above, and includes raw materials such as waste and paper which is highly damaging to the agricultural lands. The water itself has chemicals, bacteria and manufacturing waste within in which all serves to strip the minerals and nutrients from the soil. A further problem in Wadi Foukin is that they receive a lot of the wastewater that is expelled from a stone factory that was established in 2003, this wastewater contains high amounts of calcium which again causes the soil properties to deteriorate and prevents crops from growing properly. Whilst a certain level of calcium is needed in all soils, too much can prevent the uptake of any other nutrients in plants, and too little can cause acidity (Wadi Foukin Village Council, 2013). It was in 2003 that both the stone factory and general domestic waste began to be expelled, 10 years of soil damage is hard to rectify. There is currently no consistency as too how often the wastewater is discharged onto Wadi Foukin, it varies from once a week to once every three weeks, however the villagers and council have noted that the times in which they do tend to coincide with a Jewish holiday. Furthermore they estimate that every discharge is a minimum of 3,000 cubic metres which often simply sits of the land due to the layout of boundary walls whilst it slowly absorbs into the soil, hence the problem with flooding (Wadi Foukin Village Council, 2013).

The area affected by the wastewater equates to 100 dunums of individually owned agricultural land. In the village it is estimated that 60% of the population are farmers by trade, 20% of that 60% were the owners of the 100 dunums affected. Due to the loss of agriculture 15% of that 20% now have to seek work on the settlement in construction and other casual labour jobs. The other 5% held land in other areas which they are bale to cultivate instead of the wastewater affected. However, this still reflects a huge loss in income for many families. The affected land now has no cultivation upon it and the soil remains untreated due to high costs to rectify the bacteria levels. Previously 50 dunums had hosted olive trees. Each dunum held an approximate 25 trees which equated too approximately 10 tanks of olive oil produced, a loss of 50 dunums equates to a loss of 250,000 NIS for the farmers. The other 50 dunums was available for general vegetable growth and almond trees, this was estimated to have equated to 100,000 NIS, both the figures are annual estimations (Wadi Foukin Village Council, 2013). This economic loss has had a devastating impact on the village’s economy and personal family income. It has already been noted that much of the village is not involved in any economic activity which will cause poverty levels to rise.

Whilst the village is connected to the water supplied by the Palestinian Water Authority and so had no problems with contaminated drinking water, there were 2 springs that were used for irrigation purposes which are no longer viable due to their high wastewater bacteria content. Having contaminated water and soil only serves to exemplify the problems by beginning a cycle of moving the contamination further as water moves around during irrigation systems. The springs were once used for livestock (sheep), although they have now been moved and sought safer grazing ground and drinking water. Regardless, 10% of the livestock, estimated too be between 500-600 were affected which equates to a meat loss of 61,000 NIS (Wadi Foukin Village Council, 2013). Again this loss will be personal income for some of the villagers. Luckily there are no reported health problems as the council closes off the area when a discharge has or is happening to prevent anyone being near the waste and harmful bacteria’s.

The council estimate that even if wastewater were to be prevented then the soil would still take 2-3 years to regenerate itself, that would include the need for intensive soil rehabilitation techniques which would have to be carried out by a team of experts and which the council would be unable to raise the funds for. However, they also noted that even if that were to be the case they didn’t believe they would ever be able to get good prices for produce cultivated on that land as people would be suspicious as to whether it was still infected.

Nahaleen:

Nahaleen lies to the South East from Wadi Foukin bordering the Betar Illit settlement from the East. Nahaleen’s village boundaries are bigger than Wadi Foukin with 17,250 dunums of village land and a current 3898.9 dunums of agricultural land. However, only 1,132 dunums of that land are within Area B and none of the village is classed as Area A. Leaving 16,118 dunums of land in Area C totaling 93.4% of the village land under Israeli control. The settlement encroaches on 1156.2 dunums currently which equates too 10% of Palestinian land and the master plan is expected to increase that area size too 1438.1 dunums equating too 12% (ARIJ GIS, 2013). Nahaleen’s primary source of income both as a village and as individual household incomes used to be agriculture. The biggest yields were grapes, vegetables and olives. Agricultural water was largely gained from annual rainfall of which there is 700mm, but cisterns and spring water were also depended upon for field irrigation (ARIJ GIS, 2009). Nahaleen estimate that they receive two thirds of the wastewater discharged from Betar Illit onto both Wadi Foukin and Nahaleen. There are two pipes leading from Betar Illit to Nahaleen lands. The pipes are positioned atop a slight hill which allows the wastewater to flow directly down onto the agricultural land and into the spring that was previously used for irrigation purposes. The water route is visible due to the dense growth of small plants that feed off of the sewage and raw waste. The council estimates that thousands of litres are released, although accurate counting would be difficult, and the water is released every other day. The presence of the wastewater has caused the soil to degrade in quality, the minerals that were previously present have depleted and are instead replaced by hordes of harmful bacteria which any fruit or vegetable absorbs. There is visible evidence that the wastewater has killed previously healthy crops and trees, the olive trees which were positioned at the base of the route of the wastewater flow are now dead and the grapes vines which have survived had turned yellow, a visible sign of infection. Furthermore the spring which was used for livestock water and irrigation purposes stemmed from an underground source, the wastewater absorbed by the soil has infiltrated the underground water and contaminated it. The spring now harbours micro bacteria, algae and harmful insects that are attracted to the raw sewage. This compounds more problems, the insects that are attracted to the area are harmful to the crops growing there, they enter into the fruits and vegetables, both for eating and for the purposes of laying eggs. With bacteria in both the ground and in the water sources that irrigate the crops, all produce cultivated in the area is contaminated and can not be sold. The council estimates that 700 dunums of land have been contaminated by the wastewater (Nahaleen Village Council, 2013).

|

Figure 2: Yellow leaves Figure 3: Infected olives

|

This has resulted in losses of economic production, grape production has decreased by 100 tonnes per year, vegetable production has ceased entirely and olive yields have ceased as the trees are no longer able to rejuvenate themselves from the attacks of both the infected water and the insects. Many of them remain standing but with clear signs of infection including rotting olives and yellow leaves, others lie on the floor dead. Per year the annual losses for grapes has equated to NIS 250,000. Olive loss has equated to NIS 150,000 and various vegetables have equated to NIS 500,000. This is an estimated NIS 900,000 loss for the village and local families, 25% of whom were directly involved in farming and agriculture. Now only 3% of the original 25% are cultivating any land, the others remain unemployed or seeking construction work from nearby settlements. Another affected area is that of livestock, some of the local families kept sheep that were sold for milk, cheese and meat in Bethlehem. However, since the water in the spring became infected and the plants that grow around the grazing area have become contaminated people refuse to buy the meat as they know it will have been infected by the water. On average a family was able to sell a sheep for a profit of NIS 750, again this mounts up to huge income losses for local families (Nahaleen Village Council, 2013).

There have also been a series of health concerns related to the infected water. Nahaleens council reported that 15 years ago there was a small endemic of contaminated water related disease including; respiratory diseases, leather sensitivity, blisters across the body and a strand of herpes zoster which can lead to increased chances of experiencing the adult form of chicken pox known as shingles in later life. The water that’s sits infected on the top of the spoil has also begun to attract a mosquito type known as the Asian Mosquito which have been identified as a type of mosquito known for carrying disease. This could potentially lead to further health problems. To avoid the health problems the village council was forced to buy tanked water from Mekarot, the Israeli water company. Now the village is forced to pay NIS 5 per cubic metre of water, on average they consume 71,000 cubic metres per month which equates to a spending of NIS 355,000 monthly simply on water (Nahaleen Village Council, 2013). The water is appropriated from Palestinian water sources in Tuqu, essentially the Israeli’s are illegally sourcing water to then sell back to the Palestinians at inflated prices when Israeli settlements infected the Palestinian water sources. With regards to the economy, the increasing amount of money being spent on accessing safe drinking water combined with the agricultural loss represents a deficit that would be very difficult to regain.

|

Figure 4: Wastewater flowing into a spring and the algae that has grown as a result.

Figure 5: The obvious path of the water course and its location on the Israeli settlement.

|

International Obligations:

- IHL, International Humanitarian Law outlines how Israel as an occupying power has obligations towards Palestine, one of these include article 55 of the Hague regulations which states that groundwater is an immoveable asset, hence, it is protected by the rules of usufruct and cannot be depleted, damaged or destroyed by Israel.

- General Assembly Resolution 1803 (1962) reiterates the right to retain permanent sovereignty over natural resources which Israel is denying Palestine.

- Under International Water Law Israel is required to cease all activities that pollute water sources which violates the ‘no-harm’ rule codified in International Water Law.